At an orientation for the Georgia Southern Baptist Disaster Relief I was introduced to a well-established command structure called “Incident Command System.” Wikipedia defines it as,

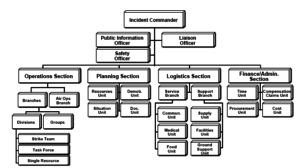

“ICS includes procedures to select and form temporary management hierarchies to control funds, personnel, facilities, equipment, and communications. Personnel are assigned according to established standards and procedures previously sanctioned by participating authorities. ICS is a system designed to be used or applied from the time an incident occurs until the requirement for management and operations no longer exist.”[1]

Essentially it is when you have people showing up to help in an emergency situation and there has to be some way to organize them. People are coming from all levels of society and having a plethora of abilities. So offices (logistics, communications, planning, finance, etc.) are established beforehand and individuals are placed into these positions in the field. Once they are chosen to a position, they are then given a notebook with procedures and predetermined tasks to be completed – and they get to work while reporting to the Incident Commander.

This system for the SBC Disaster Relief is premised on the different color hat system. At the basic and lowest level is the yellow hat. This is a person who has gone through orientation of how the overall system works, but may not have had training in specific areas (serving food, childcare, or debris removal). At the next level is the blue hat – this person is responsible for a team of yellow hats and has had training in one or all of the services offered.

This system for the SBC Disaster Relief is premised on the different color hat system. At the basic and lowest level is the yellow hat. This is a person who has gone through orientation of how the overall system works, but may not have had training in specific areas (serving food, childcare, or debris removal). At the next level is the blue hat – this person is responsible for a team of yellow hats and has had training in one or all of the services offered.

Then above the blue hats is one white hat at a given location. Coordinating and leading the overall work is the Incident Command Team chosen by the white hat. These people could be yellow hat volunteers but who may have special training in one of the needed ICS offices.

After reviewing it I am fascinated at the system’s ability to have an adequate span of control and unity of command. If someone has more than five people reporting to them then they could get overwhelmed and not be able to adequately do their job because there is simply too much to oversee. This system allows groups to continue to be divided into manageable teams.

With unity of command everyone only reports to one person. If I am clearing debris then I go to one blue hat to tell me what to do. If I have an issue, question, etc. then I can go to one person.

With unity of command everyone only reports to one person. If I am clearing debris then I go to one blue hat to tell me what to do. If I have an issue, question, etc. then I can go to one person.

I am also very intrigued by how disaster and potential chaos can be managed. Volunteers show up and they are orderly housed, fed, and put to work. Cargo and trucks full of materials and pallets of food are systematically moved in and out of a given devastated zone smoothly and orderly. Communications are set up and information begins to flow. If a given stage reaches an overly stressful level of complexity, a new layer is added to the ICS and the job continues.

_________________

So how does this apply to everyday life and in times when there are no hurricanes, alien invasions, wild fires, etc.

(1) If you respect the chain of command life becomes much easier. Just report to one person – If you find yourself reporting to more than more person, it means your system needs some adjusting. Communication is clear because you are dealing with one person.

(2) All levels of the organization are critical. The yellow hats are just as critical as the white hats – but everyone must do their job. If everyone stays in their lane and plays their part then great things could happen (thousands of people being fed a hot meal, roads cleared, and the world seeing Christ in a new way). If the yellow hats start trying to tell people what to do and play the role of blue hats then chaos ensues. Respect the system.

(3) If you are going to go into the world of chaos and change it then you need a plan. People need to know the plan (preferably before disaster hits), and it has to be simple (three colors, three hats). Imagine if there were 15 colors, shades of blue everywhere, name tags, hats, jackets, vests, all with different meanings. I can’t remember what I had for lunch much less a bunch of colors meaning different things. What we do has to be simple, memorable, and simple – did I say simple? I forgot. The more chaotic of a situation we run into, the simpler the instructions have to be.

(3) If you are going to go into the world of chaos and change it then you need a plan. People need to know the plan (preferably before disaster hits), and it has to be simple (three colors, three hats). Imagine if there were 15 colors, shades of blue everywhere, name tags, hats, jackets, vests, all with different meanings. I can’t remember what I had for lunch much less a bunch of colors meaning different things. What we do has to be simple, memorable, and simple – did I say simple? I forgot. The more chaotic of a situation we run into, the simpler the instructions have to be.

(4) This one is a little off topic, but it came up at the orientation. You are only allowed to serve three days (four at the most) before you will be sent home and replaced with another team. It is recognized that this is a long-term effort and people (even if they want to serve more) shouldn’t be in chaos too long.

What if our leaders understood that they need to be watching to tap people on the shoulder and tell them to fall out of the battle and rest. If you are a white hat or blue hat leader you need to keep watch and make sure your people don’t work so hard and so long that they hurt themselves (this is especially true if they are yielding a chainsaw). I know that I would be much more willing to be loyal to my blue hat if I know he is watching my back.

(5) The goal is clear. For disaster relief the objective is clear even before you show up. There has been a natural disaster and there are people who need help. We are Christians and have been commanded to serve and help people and then share with them the hope of the gospel (in that order). In our organizations we must make the goal clear so that others may join us. Along those same lines, the way they join in (systems) must be clear as well. If they want to be apart of what you are doing do they know how to join in?

(5) The goal is clear. For disaster relief the objective is clear even before you show up. There has been a natural disaster and there are people who need help. We are Christians and have been commanded to serve and help people and then share with them the hope of the gospel (in that order). In our organizations we must make the goal clear so that others may join us. Along those same lines, the way they join in (systems) must be clear as well. If they want to be apart of what you are doing do they know how to join in?

Here’s a link to Georgia Disaster Relief’s website if you want more information. https://missiongeorgia.org/georgia-disaster-relief/

and their Facebook page. https://missiongeorgia.org/georgia-disaster-relief/

_______________

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incident_Command_System